EJIL: Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law

Published on November 13, 2018 Author: Miriam Ingeson and Alexandra Lily Kather

On 18 October 2018, the Swedish Government authorized the Swedish Prosecution Authority to proceed to prosecution in a case regarding activities of two corporate directors within Swedish oil company Lundin Oil, and later within Lundin Petroleum, in Sudan (now South Sudan) between 1998 and 2003. The company’s chief executive and chairman could be charged with aiding and abetting gross crimes against international law in accordance with Chapter 22, Section 6 of the Swedish Penal Code. Charges of such kind carry a sentence of up to ten years or life imprisonment. The case has the potential of furthering accountability of corporate actors for their involvement in international crimes abroad.

Lundin’s alleged involvement in international crimes in South Sudan

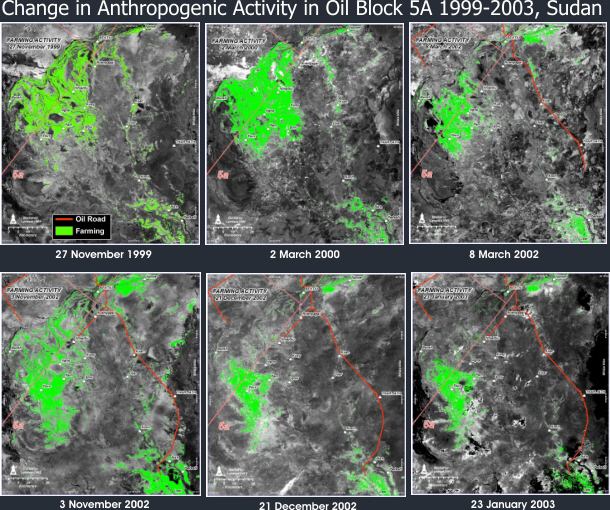

Sudan was ravaged by a non-international armed conflict which lasted from 1983 until 2005, between the Government of Sudan and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) – as well as a variety of other armed groups. Meanwhile, beginning with the signing of contracts in 1997, Lundin formed a consortium which carried out oil exploration and production in an oil concession area located south of Bentiu on the West Bank of the White Nile in Western Upper Nile/Unity State called Block 5A in the southern part of the country. According to a report by the European Commission on Oil in Sudan (ECOS), the oil exploration brought exacerbated conditions while setting off a battle for control of the disputed region, leading to thousands of deaths and the forced displacement of local populations – with the Nuer people being the most affected. Additionally, reported crimes against civilians by the Sudanese army as well as associated militias of both parties, include indiscriminate attacks, unlawful killing, rape, enslavement, torture, pillage and the recruitment of child soldiers. The consortium’s interaction with local counterparts has come under criminal investigation after the ECOS report was submitted to Swedish prosecutors in 2010. The long time span of the investigation is at least in part due to on-going conflict in the region in 2013, when the International Office of the Prosecutor had scheduled its visit to South Sudan. Furthermore, the case came with some political connotations since Carl Bildt, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sweden, had served as a member of the Board of Directors of Lundin from 2000 to 2006.

In the United States, a case comprised of a similar set of facts was brought by the Presbyterian Church of Sudan against the Republic of Sudan and Talisman Energy Inc., a Canadian oil company, which commenced its activities in the area one year after Lundin. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held in a judgment of 2 October 2009 that the claimants had failed to establish that Talisman “acted with the purpose to support the Government’s offences”. Under the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA) the plaintiffs needed to show that “Talisman acted with the – purpose – (one could argue that such mens rea standard had been set unreasonably high) to advance the Government’s human rights abuses”. On 15 April 2010, the plaintiffs petitioned for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court, supported by an amicus curiae submitted by Earth Rights International on 20 May 2010, asking to revert the decision of the Second Circuit. On October 2010 the Supreme Court declined to grant certiorari and respectively to hear the appeal in this case. In contrast to the rather broad universal and extraterritorial jurisdiction provided for in the Swedish Penal Code, the Supreme Court decision in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, Co. remarkably restricted the application of the ACTA in cases involving allegations of abuse – outside – the United States by finding that presumptively it does not apply extraterritorially.

Nevertheless at the European level, corporate accountability for atrocity crimes and gross human rights violations is beginning to gain traction as the potential international and national the regulatory systems, previously deemed insufficient and underutilized, shift into gear. In the United Kingdom, as a result of a lawsuit filed by Leigh Day on behalf of 142 Sierra Leonean claimants, investigations are under way against the mining firm Tonkolili Iron Ore Ltd and its parent company African Minerals, alleging complicity in police crackdowns in Sierra Leone in 2010 and 2012. It is further worth noting that a significant contribution to corporate accountability for international crimes is currently carried out in France and may be of interest to the Swedish judiciary. In June 2018, three French investigative judges have indicted the multinational Lafarge (now LafargeHolcim) for complicity in crimes against humanity committed in Syria. In that case, brought by Sherpa and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, eight former top executives of the group have been personally charged with crimes including endangering people’s lives in relation to the activities of the group’s cement factory in Syria between 2012 and 2015.

Sweden’s universal jurisdiction legislation

It is the duty of every state to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over war crimes amounting to grave breaches of international humanitarian law. The legal framework available to Swedish prosecutors in fulfilling the obligation is Chapter 22 Section 6 of the Swedish Penal Code (Brottsbalken), which applies to international crimes committed before 1 July 2014 – such as the case at hand – and the Act on Criminal Responsibility for Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, and War Crimes which constitutes the substantive law for international crimes committed after 1 July 2014. The latter legislation was enacted primarily to better reflect recent developments of international criminal law primarily emanating from Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). It follows that international crimes consisting in war crimes committed before 1 July 2014 are prosecuted under the Swedish Penal Code as “crime against international law”. The crimes can be prosecuted on the basis of universal jurisdiction as provided for in Chapter 2, Section 3 (6) of the Swedish Penal Code, regardless of the nationality of the perpetrators or victims and the place where the crimes were committed. The list of prohibited acts in Chapter 22 Section 6 (1-7) is non-exhaustive, and the provision also explicitly covers any serious violation of a treaty or agreement with a foreign power or an infraction of a generally recognised principle or tenet relating to international humanitarian law concerning armed conflict. The provision thus incorporates international humanitarian law by reference to these sources of law in international law (renvoi). A case of civil liability against the suspects or a third person may be brought in conjunction with the prosecution of the offence, as stipulated by Chapter 22 of The Code of Judicial Procedure.

Approval to prosecute

While authorization from the Swedish governmental authorities is not required to prosecute crimes committed on Swedish territory, it is required where indictments involve extraterritorial jurisdiction, save for where there is a clear link to Swedish or inter-Nordic interests. The government’s authorization is a necessary procedural condition, but it is not, however, part of the judicial process per se. This explains why the government’s appraisal is not based on the merits of the case, but on a rudimentary test of proportionality. The provision requiring authorization does not provide explicit criteria for the test, which is at the government’s discretion. According to reasons stated in government decisions, the test will usually consider the type and importance of the nexus to Sweden and the severity of the alleged crime.

The requirement of authorization is due to the structure of the rules on extraterritorial jurisdiction enshrined in the second chapter of the Penal Code. Chapter 2, Section 3 provides for extraterritorial jurisdiction for war crimes based on the universality principle, as well as for any grave crime carrying a minimum penalty of four years in prison. The latter category enables Sweden to fulfill obligations in international cooperation and proactively pursue violations of national interest based on the passive nationality and protective principle. Combined with the absolute duty to prosecute that applies to Swedish prosecutors, the unmitigated effects of such a rule on its own would result in transgressions of international law on jurisdiction and overburdening of the judiciary. As for the atrocity crimes, exercising criminal jurisdiction based on the universality principle is compliant with international law. Nevertheless, procedural and practical difficulties could stem from several states seeking concurrent jurisdiction, for instance the territorial state or third states claiming a direct interest based on the nationality of victims. The authorization as provided for in Chapter 2, Section 5 of the Swedish Penal Code, is thus the second step in a two-tiered test, designed to balance the effect of the relatively wide scope of the general rules to address such conflicts of interest. The provision stipulates that as a general rule and subject to a list of exceptions with a clear nexus to Swedish and inter-Nordic interests, offenses committed abroad may only be prosecuted after authorization by the government, or by delegation, the Prosecutor General.

The exercise of extraterritorial jurisdiction is inherently political, which on the one hand is why a procedure involving government authorization is not surprising or entirely uncalled for. On the other hand, and even though the government does not rule on the merits, vesting the government with such discretion in a criminal investigation inevitably raises issues of arbitrariness and places the independence of the judiciary in dispute. Consequently, a pre-study within the Ministry of Justice proposes a future modernization of the legislation by placing the power of authorization primarily with the Prosecutor General instead of the government.

Next steps

Authorization down, the prosecutor has yet to serve the defendants final notice of the investigation, and allow for a reasonable time for counselling before proceeding to the decision on whether or not to prosecute. Given the presumed size of the investigation, this could mean a lengthy period of time.

If and when the prosecutor decides to proceed with prosecution, there is no shortage of legal issues to be addressed. The method of incorporation by reference reflects the dynamic nature of international criminal law, while presenting the judiciary with a considerable challenge of interpretation as to the applicable international law. The Act on Criminal Responsibility for Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, and War Crimes of 2014 is based on incorporation by transformation into explicit material elements in domestic law, which serves to alleviate some of the interpretative challenges in the future. Other issues are likely to remain, such as how to adequately assess individual liability within corporations for the crimes concerned. When assessing individual liability within corporations Swedish judges routinely turn to general principles on perpetration and complicity, as codified for instance in Chapter 23, Section 4 of the Penal Code, which states that punishment as provided for an act shall be imposed not only on the person who committed the act but also on anyone who furthered it by advice or deed. The reference to “the person who committed the act” may be interpreted as encompassing co-perpetration, by fully or partially contributing to the actus reus. “Furthering by advice or deed”, amounting to aiding and abetting, does not entail making a significant contribution to the crime, but may instead be acts of little or no consequence to its success. (As a comparison, the ICC has taken the view that for the purposes of adjudication according to the mandate of the Court, establishing significant contribution is necessary although it is not expressly required in Article 25(3)(c) of the ICC Statute). Furthermore, the conceptually underdeveloped doctrine of liability for corporate directors for omission of due diligence may be alluded to in the assessment of corporate crime in Swedish courts. Although it escapes more precise definition, the core of the doctrine serves to identify a physical perpetrator of criminal acts consisting in omission within a corporation. The crimes for which the assessment is relevant tend to fall squarely within the realm of economic activity, such as tax crimes or minor infractions of regulations of manufacturing. Crimes against international law, on the other hand, have only ever been tried in a handful of cases and never in a corporate setting. The theory of individual liability for crimes within corporations is in dire need of conceptual development in Swedish law, and particularly so for the crimes in the realm of international criminal law. The contribution of a case combining these two aspects would be substantial, regardless of the outcome. It could further serve as a sound starting point for discussions around corporate criminal liability, conspicuously absent in Swedish legal theory. An indication that the case will have a considerable conceptual impact in that respect is the announcement on 1 November 2018 by Lundin Petroleum that the company has been notified by the prosecutor of a potential corporate fine and possible forfeiture of economic benefits in relation to the operations in Sudan. A corporate fine is not considered a penalty for a crime but is an extraordinary legal remedy serving as a repressive sanction supplanting corporate criminal liability. The corporate fine and forfeiture would likely be tried alongside any future individual indictment, placing the corporation next to its directors in the courtroom.

The slowly growing body of case-law from domestic courts on atrocity crimes in relation to corporations provides an opportunity for the legal community to gain a better understanding of the concept of corporate criminal liability, individual and organizational. The potential ending of impunity as domestic courts tentatively take this road less traveled also raises the hope of future restitution and compensation for victims. To survivors of atrocity crimes, that could make all the difference.